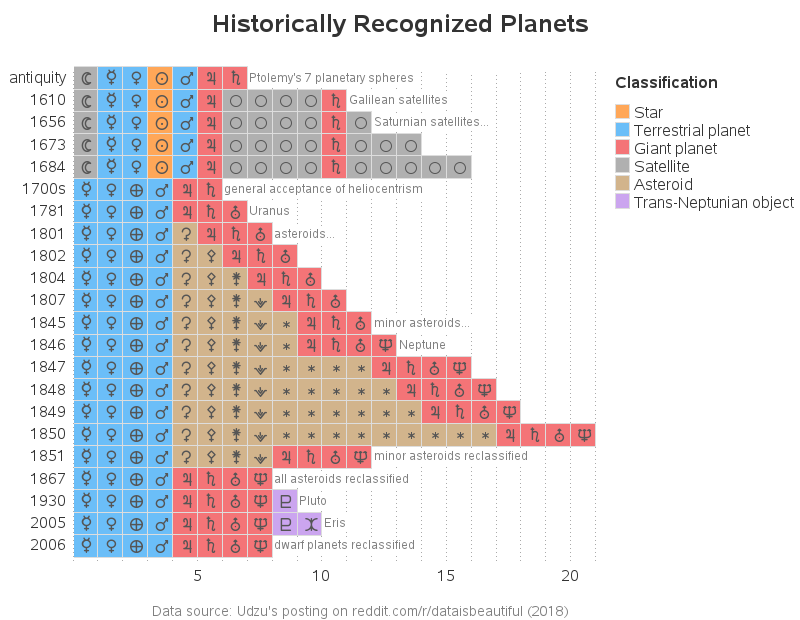

| The seven classical planets were known to the Babylonians, and were named "wanderers" by the Greeks since they moved across the sky relative to the fixed stars. These are also the source of the names of the seven days of the week: Saturday (Saturn), Sunday (Sun) and Monday (Moon) are still obvious in English, while Mardi (Mars), Mercredi (Mercury), Jeudi (Jupiter), and Vendredi (Venus) are clearer in French. |

| The satellites orbiting Jupiter and Saturn were initially described as planets too, even by Copernicans such as Galileo ("I should disclose and publish to the world the occasion of discovering and observing four Planets, never seen from the beginning of the world up to our own times"). Furthermore, the Copernican model was not widely accepted until the 1700s - not for theological reasons, but because at the time it was still scientifically unsound (its problems with stellar parallax, rotation inertia, and circular orbits had not yet been solved). |

| The early asteroids were also considered planets, and assigned planetary symbols. Following the rush of discoveries starting in 1847, symbolic notation was dropped for the minor asteroids, but only after over a dozen had already been assigned. The four big asteroids (Ceres, Pallas, Juno, and Vesta) continued to be listed as planets until the 1860s. |

| Pluto was widely considered a planet, and Eris was briefly described as a tenth planet by NASA following its discovery. However, Chiron was only described as a planet by the media and astrologers, and Charon was never officially considered part of a double planet with Pluto. |